The following article was published in the July 2021edition of The Schubertian, journal of the The Schubert Institute (UK).

Moments of genius that announce their presence with brass fanfares are notable for their extreme rarity. Usually unobtrusive, they are often found hiding in plain sight, embedded in masterworks like tiny gems perfectly set in a beautifully fashioned crown.

Thus far, no allusion to this feature has been found in the academic literature, nor has it been mentioned in performances or broadcasts. All individuals with whom this information has been shared have declared that it was new to them.

..........................................................................................

A motivic connection in Schubert's Winterreise

Delacroix's lament that all his days led to the same conclusion, “an infinite longing for something which I can never have," haunts every page of Schubert’s Winterreise. Perhaps it is not an accident that the icy bleakness of the first four songs is barely dispelled by the sunlit image Schubert creates at the opening of the fifth.

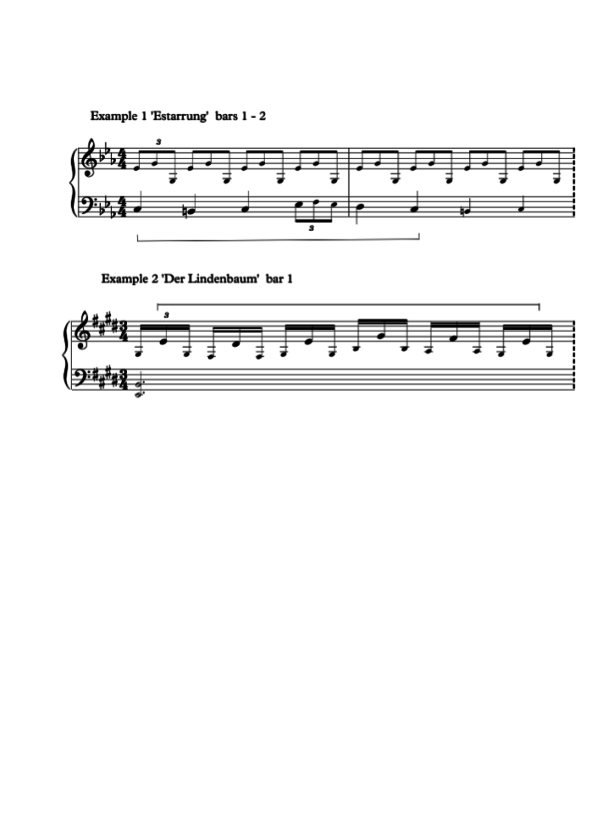

The connection between the fourth and fifth songs provides both a tantalising glimpse of genius at work and a telling insight into the psychological impact of the fifth song when heard in its proper context. The two extracts given below share some interesting characteristics:

1) The position of this link, occurring between the minor keys of the first four songs and the first song in a major key, is clearly structural; it is pivotal in the context of the cycle as a whole.

2) The thematic outline (allowing for tonality) is precise.

3) The two themes are placed virtually back-to-back, since the material in Ex 1 also forms the postlude, followed immediately by Ex. 2.

4) The simultaneous translation of the triplet figures of ‘Erstarrung’ into those of ‘Der Lindenbaum’ is also highly significant.

At no point in the history of Western classical music has the motif not been the go-to implement in the composer’s toolbox. In whatever form it manifests, its usefulness has conferred upon it a ubiquity that transcends the particulars of period, time and place, to the extent that it is both practically and philosophically legitimate to ask: where does the motif end and the composition begin?

Such thematic or other internal relationships as may be found to exist in the work of lesser composers might justly be considered inconsequential or trite, not worthy of further investigation. The best exponents of the science of composition present, of course, a different case. The question as to what percentage of this particular masterstroke can be attributed to subconscious instinct as compared with conscious engineering is intriguing, especially given the apparent effortlessness of Schubert’s melodic gift.

Considering its position in the cycle and that no other two songs appear to have been paired melodically and rhythmically in so precise a way, the balance of probability would seem to lie in favour of the linking of the two songs being deliberate and conscious.*

* In a casual recital setting, there is a strong case for the two songs to be routinely performed as a pair, and even for the triplets of both songs to be played at roughly the same pace.

The six-note melodic motif - complete, and with variants - is also employed as the principal element in the formal structure of both songs, strengthening the musical and psychological bond between them. It should be further noted that the triplets of ‘Erstarrung’ accompany the motif, whereas those of ‘Der Lindenbaum’ state it. The conjoining of the triplet figures of both songs with the motif in this way, coupled with the transformation of their function in relation to it, is remarkable enough; but it is their simultaneous employment as the chief agent by which is created the extreme contrast of mood from the one song to the other that elevates the linking of these songs above the purely functional.

The linden tree calls to the wanderer from a distant place, a spectral summer whose sunlight brings no warmth. The memories cast by its shadows, far from defrosting his heart, only plunge it deeper into the freezer, further back into the wintry depths of his grief. ‘Der Lindenbaum’ is, if anything, more chilling than Estarrung because it captures the terror of loneliness not in the expression of breathless desperation, but in the evocation of a gentle breeze on a warm summer’s day: the link has done its job, carrying the weight of sorrow in a seamless transition from one song to the next.

There remains the nagging question of why what is revealed by the notes in the score, however ingenious, fails to explain the impact of these two songs when placed side by side; how they can be so very closely bonded and at the same time so very different.

To date, despite the efforts of neuroscientists and apologists of material and intellectual philosophy, the universal appeal of great artistic moments and works - the hold they are able to exert on the mind and imagination - remains unquantifiable. The explanation for the effect of certain passages of music seems to lie forever just out of reach. The effect is real enough, but its cause is not to be found, tested or proved.

It is in the music, to be sure, and yet it is not! It’s a will-o’-the-wisp, a phantom, a quantum phenomenon that can be both wave and particle, positive and negative at the same time, and only becomes physically real when actually observed. Something existed in the empty silence that proceeded from ‘Erstarrung’, something non-mechanistic whose nature only Schubert could observe, understand, and then distil into the opening passage of ‘Der Lindenbaum’.

Nick Capocci